Cristina Casagrande and Eduardo Boheme

Leia a entrevista em português.

In the pantheon of Tolkien scholars, one can find an experienced professor with an elegant and distinguished bearing. It may well be that, in a playful comparison with Tolkien’s world, she could be called a Maia, perhaps a Fay, since her wisdom dates back to the Elder Days of Tolkienian scholarship.

Back in the also beautiful and enchanting Primary World, Verlyn Flieger is Professor Emerita in the Department of English of the University of Maryland, and among her areas of expertise are Tolkien (whose works she has been reading since 1956-57), Mythology, and Folklore. She currently teaches online courses at Signum University, is a coeditor of the renowned journal Tolkien Studies and a member of the Walking Tree Publishers’ board of advisors.

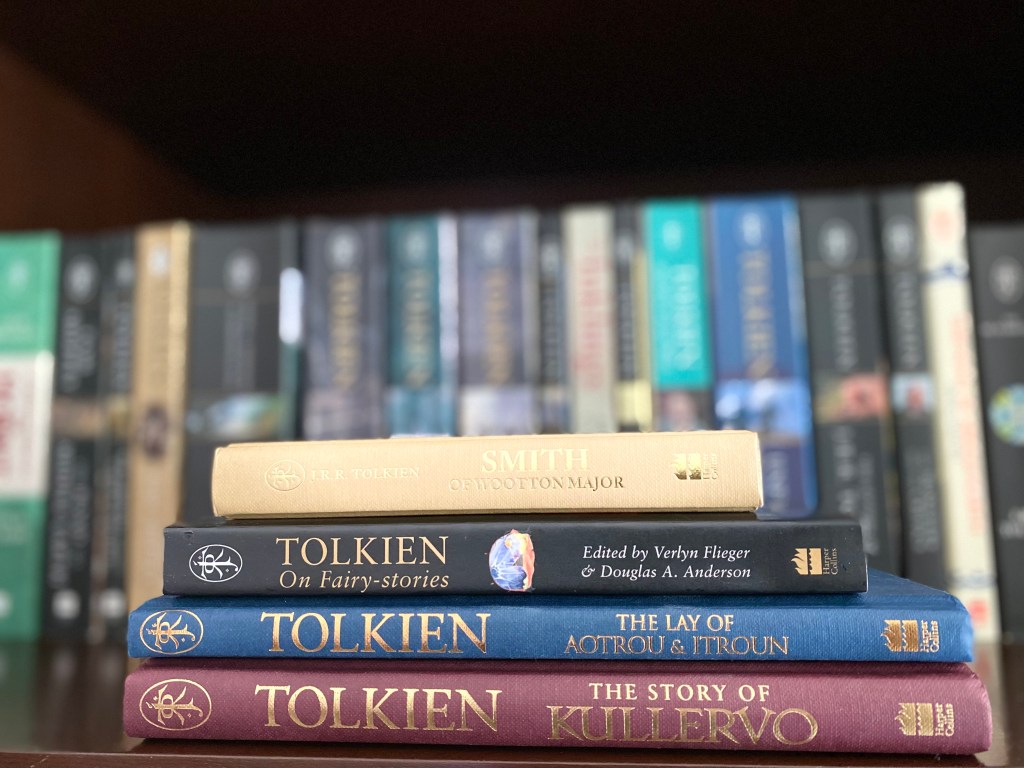

Her many great academic deeds in decades of scholarship include winning the Mythopoeic Awards four times and the responsibility of editing some of Tolkien’s own works, such as Smith of Wootton Major (2005), The Lay of Aotrou & Itroun (2016), and The Story of Kullervo (first published in 2010, in Tolkien Studies, and as a stand-alone edition in 2015).

These and other contributions not only guaranteed her a spot among the great experts in Tolkien’s works, but also a life experience that goes beyond her profession. Flieger was friends with Priscilla Tolkien, Ronald and Edith’s youngest child, and corresponded with Christopher, Tolkien’s third son and literary executor. She has also delved into the fictional world herself, writing fantasy books with Celtic and Arthurian themes.

An inspiring figure for many Tolkien researchers, Flieger was also inspired by other scholars, such as Tom Shippey, Owen Barfield, and Christopher Tolkien. Having published her first academic book in 1983, Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien’s World, she is still writing articles, prefaces, and other works related to Tolkien and fantasy, the most recent being “Defying and Defining Darkness” (Mallorn, Tolkien Society, 2020).

The launch of The Great Tales Never End: Essays in Memory of Christopher Tolkien is scheduled for September 2, 2022. In this new book, many tolkienists contributed with scholarly essays in their own field of inquiry, Flieger among them, with her essay “Listen to the Music”.

Check out our interview with her.

You have important works on fairy-tale studies. Do you think your perception of “fairy” (in its multiple meanings) has changed over the years? How have Tolkien studies contributed to that?

Do you mean both “fairy” and “faërie”? My perception has deepened as I’ve dug into the etymology, and the drafts of Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy-stories”. Tolkien called faërie a “perilous realm” and I would agree. It has a dark side; you can lose yourself in enchantment. I think Tolkien was aware of this, and it shows in a careful reading of The Lord of the Rings. And even in The Hobbit. Mirkwood is a dangerous place.

You have edited many of Tolkien’s own manuscripts, such as The Story of Kullervo, On Fairy-Stories, Smith of Wootton Major, and The Lay of Aotrou & Itroun. What must an editor be ready to deal with when facing a Tolkien’s manuscript?

His handwriting first of all. Tolkien used several scripts, ranging from a beautiful, calligraphic hand (when he was making a fair copy), to an undecipherable scribble when the ideas were coming thick and fast and he was hurrying to catch up with them. There have been words and sometimes whole sentences, especially in the drafts of “On Fairy-stories” that I simply could not read.

Could you please tell us briefly about the experience of editing the abovementioned works? Which of them gave you a greater sense of achievement as a researcher or even as a Tolkien reader?

Each of them was simultaneously a challenge and a pleasure. A challenge because the responsibility to serve Tolkien’s intentions (where I could discern them) always weighed heavy. The stories, Kullervo and Smith and A & I were the most fun, as I got caught up in the shifts and changes in plot and character. Of the three, I think The Story of Kullervo gave me the greatest sense of achievement because it was a new work, where the others had been published already. Nobody had seen the Kullervo side of Tolkien, his affinity for this very dark, tragic, self-destructive figure. I think it enlarged our sense of what he was capable of.

How would you assess Tolkien studies nowadays, especially if compared to the academic scene when you started your career?

There wasn’t really much of a “scene” when I started. There was Tom Shippey, Jane Chance, Anne Petty, Paul Kocher. So I was able to use broad strokes, look at large subjects like Tolkien’s medievalism, his ideas about language. And of course, The Silmarillion had only just been published, and that opened a whole new window, put The Lord of the Rings into a newer, wider perspective. Now there are many more and different areas of study, the languages, queer theory, race, sex, politics. The areas are splintered into more discrete and specific divisions of study. There are also more good scholars whose work can be joined or built on. Minds enrich each other; the more minds the greater enrichment. Plenty of room.

Tolkien studies cross different areas of knowledge, such as philology, theology, mythology, and other aesthetic and literary issues. In your opinion, what field of knowledge has been the most prominent throughout the years in Tolkien studies and how could these areas work together harmoniously?

They are all important, but to different kinds of readers and for different reasons. They do not always work in harmony with one another. Theologists and mythologists, for example, tend to look for and to find different values in his fiction. Have you read Claudio Testi’s Pagan Saints? It’s a very good, balanced discussion of this rather vexed topic. Tolkien’s languages are themselves a complete field of study, but a very technical one requiring some background in linguistics for understanding. It’s a relatively narrow area and attracts mostly language buffs.

Do you think the movies, series and other adaptations significantly interfere with academic research?

I think they redirect it. They change the medium and that changes the material and that changes how it is seen.

This year Priscilla Tolkien left us, and Christopher passed away two years ago. What do you think will be different from now on regarding Tolkien’s works, studies, and adaptations?

I think there will be more adaptations (some are already in the works). The books themselves will be less seen as standards than as springboards for further invention. I don’t altogether welcome this, but I’m sure that’s what will happen.

What advice would you give to the younger researchers on Tolkien, especially the ones who are in the very start of their academic road?

Find what excites you and write about it. Tolkien’s work is so rich, so multi-valent that there’s work to be done on every level. Research is ongoing, one idea leads to another, one concept or scene or sequence or sentence or word ignites the next one. Follow the trails where they lead.

(Photo: Tolkien Society)

1 thoughts on “Between darkness and the splintered lights of Tolkienian Faery: an interview with Verlyn Flieger”